Day 71 - I thought you said there would be downhill?

Rising late from the “campground” at Mono Lake Basin, we departed quickly, eager not to give Gloria anymore money. There were several options for breakfast up the road and we set out for Lee Vining where we would be able to change into fresh clothes and have a cup of coffee before starting the big ascent of the day. For the past 2 days, everyone who has seen us has asked us whether we were participating in the “Death Ride” a 100 mile ride that went up and down 5 summits totaling more than 14,000 feet of climbing. We have replied “no” very politely each time and then been lectured on what an amazing ride it is by the person who stopped us. We go on to tell them we would not be participating in a race like that with 100 pound bikes and that maybe we will consider it for the future. Particularly entertaining, is when they tell us what a challenge it is, owing to the high elevation and thinned atmosphere. The climbing is the real challenging part, not the distance they tell us. We are well acquainted however, with both of these obstacles. Having been 4000+ feet above sea level for the last month we have topped out near 10,000 feet a handful of times. Thanks to the gradual acclimatization (because our bikes are so slow), we have been able to avoid the dreaded altitude sickness that many warned us of. (except for the last mile or two of the Colorado pass (Monarch?) when Gen thought she would throw up, but was able to keep it down by thinking “I need these calories, I can’t waste these calories)

Today was due to be our longest contiguous climb on the trip, starting from the basin floor before breakfast we would have a short flat stretch before our turn not Highway 120, up over Tioga Pass. Going through Yosemite was not part of our prescribed Adventure Cycling Association (ACA) route. However, 9/10ths of our trip was ‘off route’, and we had enjoyed those parts tremendously. Still, the climb was long and sustained and the roads were fraught with peril, should the internet bike forums be believed. Gen was concerned, as people warned her left and right of the potential for being pancaked by an unwieldy RV rental. The road was characterized as narrow, arduously steep, and highly trafficked by vacation tourists. The total rise from the turnoff to the summit was nearly 3,000’ and the length a paltry 12 miles; which for you arithmetic wizards, would mean an average of 250’ of elevation, per mile. Our elevation profiles had warned us of an average grade 5.2% with a peak grade projected at 14%. Gen was less than excited by the prospect of having to tack in traffic.

After a large meal of pancakes and eggs we started our march towards the turn-off for 120. Since Carson City I have felt an inexplicable energy. All of the languor has been removed from my stride and in its place an inexorable excitement. I’ve felt faster and stronger in the last two days than anytime previously on the trip. While my legs are no less sore, and my butt still aches I’ve felt like there is no distance too great or hill too steep. Every turn of the pedals yesterday was a revolution closer to Yosemite and this excitement catalyzed the next turn. Like some critical rate-limiting step I had passed some threshold that left me feeling pulled yanked towards the park.

Last year, two days after my birthday, I drove from Boston, Massachusetts to the Tahoe border of California with my good friend Chris Wood. He needed his car on the west coast for the approaching year of dental school and we had spent months discussing the prospect of climbing in the Sierras. His time at the BIDMC was coming to a close and he had all summer to have adventures but I had little more than a week. Owing to the tight schedule we wanted to waste as little time as possible with our travel. We set out and drove non-stop from Boston to Tahoe in 54 hours. Our longest stop had been to eat and shower at a friend's in Salt Lake City. Other than that, stops were limited to combined bathroom, eating, fuel breaks. This started out manageable and grew to become pretty unpleasant around Nebraska when the air-conditioning ceased to function and we were left driving like sweaty peasants with only the wind to cool us. Driving and sweating and sleeping and eating and driving left us soiled and stagnant as we motored along.

When people tell me their stories of driving across the country I am impressed by all the sights they recount and memories they retained. For me, driving across the country was a blur punctuated by memorable blips in an otherwise inaccessible fog. I do remember meeting Chris's friends Patrick and Julie for dinner at a brewery and photographing the sunset over the mountains in Salt Lake City. We were joined by Patrick's, Black Diamond coworker, Kevin and his girlfriend and he regaled us with stories of climbing in the valley and all of the things we should try to get on. Kevin was animated and bounced around with a vicarious excitement for our trip and the climbs we would be attempting for our first time. With more route-beta and suggestions than I could ever fit in my head but a genuine gratitude for the eagerness and confidence Kevin had for us, we shook hands and I thanked him as we parted ways.

Tragically, Kevin was killed in a rock climbing accident later that summer and I was never able to share with him the wonderful time Chris and I had getting shit-our-pants-scared on the various 'easy' classics we pursued. There's no real consolation to tragedy. People offer generic platitudes like "he died doing what he loved" or "he lived so much in what time he had" but the reality is it sucks when just about anyone dies. Kevin is no exception and I am grateful I was able to meet him and share a few drinks and conversation. He was particularly insistent that there was no reason for him to climb anything else in the Valley so long as El Cap was around, characterizing it as "the sweetest, cleanest piece of granite in Yosemite" Pantomiming hand jams as climbers are apt to do, he fantasized aloud at the joy of plugging up the Stovelegs, hand over hand.

Chris and I took his words to heart though and had an absolute blast exploring a large variety of climbs; dike-hiking Lover's Leap near Lake Tahoe, knob pulling in Tuolumne and stuffing granite cracks in the Valley. That summer trip was in many ways like this one. I've never really shown a talent for practice and in life have preferred the trial by fire. I figure if I can learn something at the harder levels, the knowledge will come faster as a side effect of necessity.

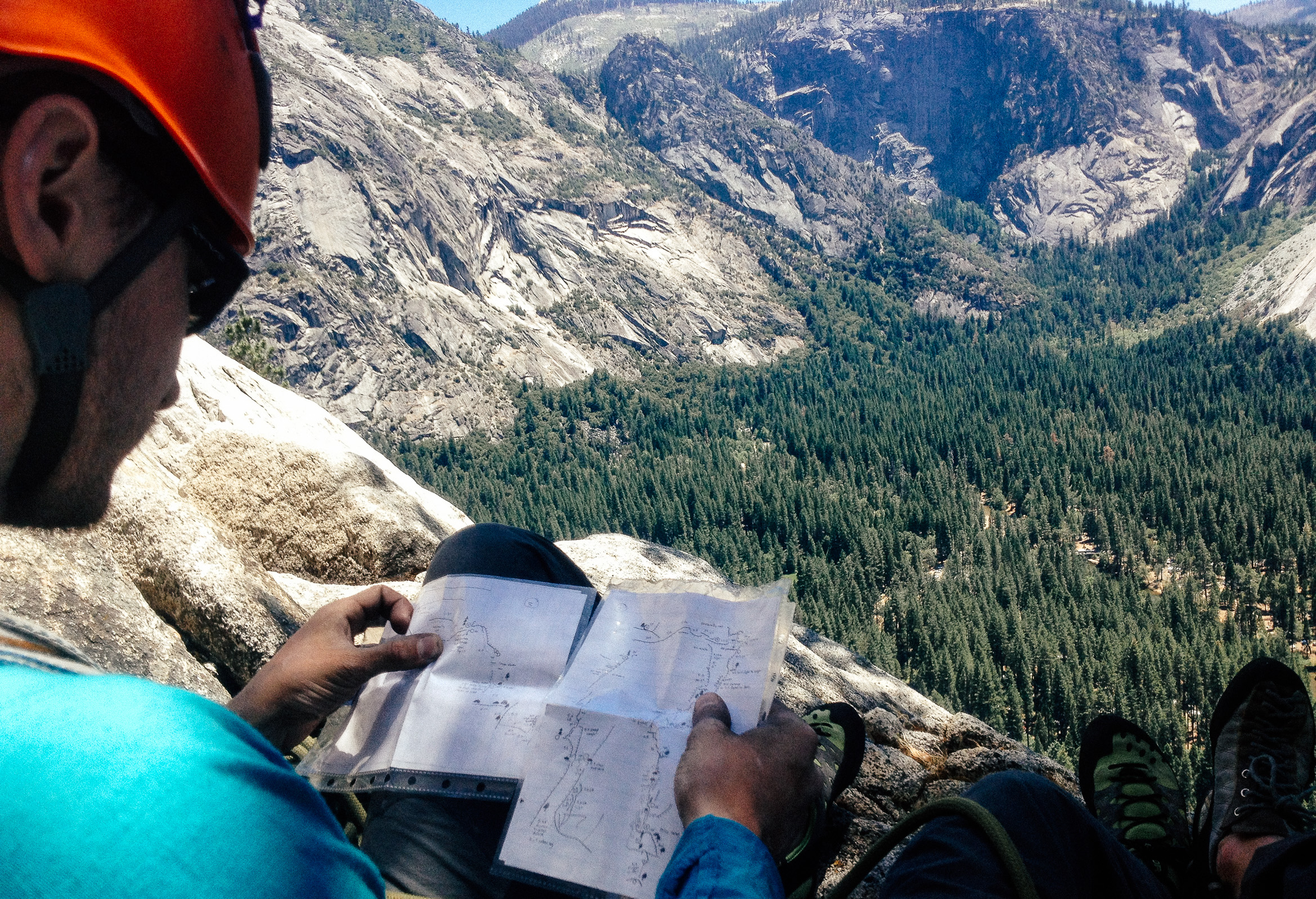

Prior to leaving with Chris, I had only done a single climb more than 5 pitches (rope-lengths) long and the majority of my multipitch experience took place in the novice-friendly Shawangunks of central New York. While I had been climbing for years at this point, I had never led a traditional climb, plugging my own gear. In the course of the trip I ended up with more vertical mileage outside than I likely had in the past several years prior to the trip. With ascents of Snake Dike on Half Dome, Royal Arches, Cathedral Peak and many others, my exposure to exposure was doled out in a merciless flood rather than the petering trickle I had become accustomed to.

By the end of our day on Royal Arches, we had done close to 20 rappels a piece to reach the ground. Hanging on bolts at the 2nd rappel station with more than a thousand feet of air below us was an experience I wouldn't have believed before the outset of the trip. Chris took the reins throughout the duration of our time out west, leading almost every pitch we climbed. I was only too happy to be a seconding, belay-slave but when I got home I couldn't wait to explore on my own.

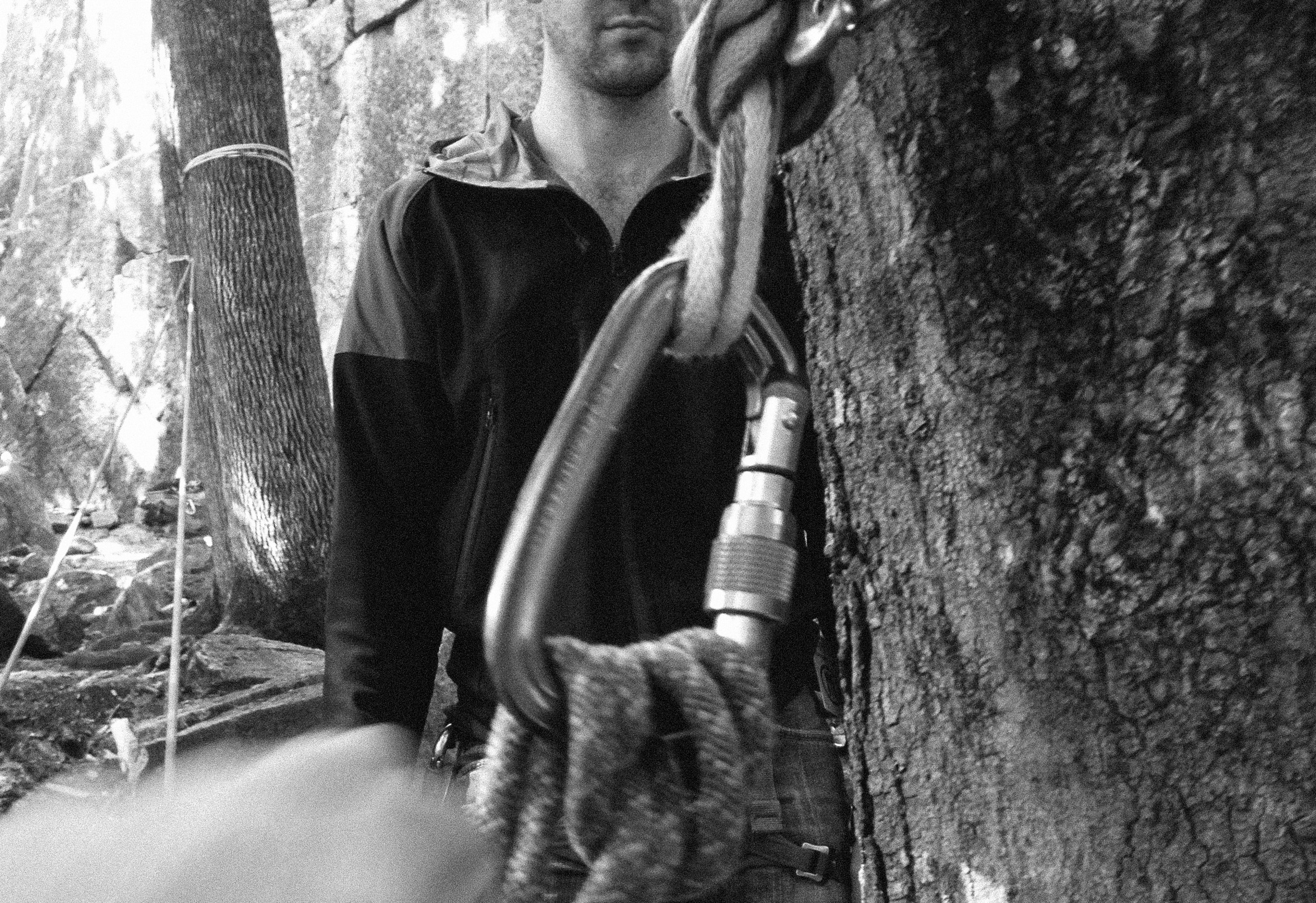

I signed up for a self-rescue class figuring that it would be prudent to at least have some modicum of escape know-how. Enlisting Karl James' company, we drove up to the Whites in New Hampshire where the class was being taught by the incredibly knowledgeable, Mark Synnott . Figuring it would make more sense to arrive the night before and not drive in the morning we went up toward North Conway with no sleeping arrangements planned. Sans tent and sleeping bags we elected to sleep in the parking lot in our Great Aunt's Ford Taurus, a car that was designed even less for sleeping, than for fuel economy and style. In the morning we met up with Mark and another group of three and listened and rehearsed as Mark instructed. We learned a variety of techniques for self-rescue, and drilled escaping belays and hauling unconscious bodies. It was all in all a fun day and we left feeling slightly more confident in our ability not to get ourselves into a pickle.

The following weekend I told Karl we would go to the Gunks and put our new-found skills to the test on real rock. Trusting his older brother against all common-sense and self-preservational instinct, he agreed. The night beforehand, my father, sensing an opportunity for free labor, goaded us into scraping the dormers on the roof while the wasps weren't active. We hiked up one side of the roof and self-belayed down the other and scraped furiously in the cool evening air.

The next day we drove to the Gunks and immediately set out to conquer some easy trade routes. With a few 5.2's through 5.4's picked out I was confident the day would be relaxing and fun. After a quick hike up the glorified scramble Easy Keyhole we walked off and started up a 5.4 nearby. Knocking the next climb out in short fare, we did a couple other short single pitch routes and then set off to finish the day with the classic Three Pines. Karl had still only done a handful of traditional multipitch climbs and I was eager to try my hand at something that was a little longer. Heading up through the first pitch the gear was sparse but the climbing was laughably easy. It wasn't until you got up through the first series of ledges and were forced to traverse right out onto the face that it really felt like you were climbing. The Gunks have a wonderful ability though, to make 5.3 terrain dead vertical and leave you with so much air behind and below you, that you could swear you were ten pitches up instead of two. We did the second corner pitch and Karl remained in good spirits, an excellent sport considering his roped escapades had been fraught with terror in the beginning of his climbing career.

I felt electric, blissfully engaged and satisfied and just overcome with delight. Stepping out over air onto the surfboard on the third pitch, the typical fear I have when leading was utterly absent and I felt fluid and calm. I pulled across the traverse and up around the corner. The majority of the technical difficulty and exposure was behind me and I was awash in a surge of happiness and accomplishment. I charged up the final 80 feet, opting to link pitches and cruise through the harder direct variations towards the top. I belayed Karl up to the anchors and we high-fived. Absurd as it sounds, climbing 5.3 was the most satisfaction and fun that I have ever had climbing. It also marked the first time that I can honestly say I really felt like a climber (after 7 years!).

My first day leading climbs at the Gunks with my brother Karl, while on some of the easiest terrain available, was probably my most memorable day of climbing ever. Prior to this every outing had been either seconding someone else on trad climbs, bouldering or leading established sport routes. The thrill of route-finding, personal responsibility and evaluative decision making was the most liberating experience I'd ever had outside. Combined with the feeling of immeasurable success, standing on the top of those 5.3 and 5.4 classics, I was glowing with personal accomplishment and an inextinguishable feeling of freedom.

It is a feeling unlike anything else I've ever experienced and I can't imagine I ever will again. That sense of agency was heightened by consequence and while long-distance biking carries a great deal of risk the majority of the time it is (thankfully) low-danger. We celebrated as all things should be celebrated, with burritos and beer and drove the hour and a half back to Connecticut eager to return.

--- The frustration of fitness

The next morning my elbow ached with a persistent dull pain that grew when flexed against. The pain had occurred with mild intensity while top-belaying my brother on the previous day's climbs but now it hurt despite absence of movement. It was not a new pain, for the past month and a half, it had hounded my exercise sessions at the gym and left me uncomfortable the following days.

In climbing, like most sports, you get used to your body hurting. You learn to work through pain because it is a perpetual accompaniment to exertion. But there is good pain and bad pain, appropriate pain and problem pain. Hurting, when you are pulling down really hard on small holds, is part of the game. It's like your ass being sore after being in the saddle for 10 hours straight. Typically however, those pains subside with rest and removal of strain. The elbow issue was starting to dog me regardless of activity and ache during regular daily movements such as opening doors. It was time to consider the possibility that I had done something really bad.

For the two months prior, I had been attempting to learn free-standing handstands by doing a hundred handstand push-ups a day against my wall. By the end, I had enough strength to press-up out of a headstand and walk several paces on my hands. But going from no activity to massive activity is never a good plan and my triceps tendon inflamed in revolt. Unaware of its unwillingness to cooperate, I continued my exercises and exacerbated the insult.

Looking for answers on how to fix the damage I had done, I contacted my orthopedist and requested a visit. We scheduled for later that week and I went in.

Diagnosis: Tricep Tendinitis

The X-Ray had shown no indication of fracture or spurs and the orthopedist had suggested that it was likely an overuse injury. She noted inflammation at the insertion point of the triceps tendon and told me it would require immediate rest. No more climbing. She put me on a daily regimen of NSAID's and said it would likely be a month before I was able to resume exercising. A month passed and the pain persisted. She told me to take the next 3 months off and cut out other activity as well.

Going from from feeling like you are at peak fitness, to ceasing all of your regular physical activity is an infuriating experience. Unable to use my right arm and unwilling to take up left-handed bowling I was left with running, an activity I've historically despised. Learning to unicycle with my friend Julia was in large part fueled by my inability to do much else.

I waited and waited and waited and the pain didn't subside. By December it had been almost 4 months and no discernible improvement had occurred. I paired my rest with physical therapy, and then occupational therapy with an OCS certified therapist.

-

Stretching

-

Ultrasound

-

Electrical Stimulation

-

Iontophoresis

-

Deep Tissue Massage

- High Rep, Low Weight exercises

We did it all and then some (skipping only cortisone injections which I was recommended against). Right up to the week before I left for the bike trip, I was trying to condition my elbow and recover from this lingering issue. In the end it was fruitless and my elbow feels much the same now that it did before. It's been a year since I was able to climb without pain and 10 months since I was able to climb at all and I can't express how frustrating that experience has been.

In many ways, my inability to climb was the spark that ignited my desire to bike cross-country. Without climbing, I felt helpless and sedentary. Cycling offered a means by which I could do something exciting and big despite my upper-body limitations. There's always a silver-lining I guess, or you turn lemons into lemonade or some other tired cliche. Maybe it's just that you keep moving if you can't sit still, no matter how you manage keep yourself in motion.

---

We turned onto 120 and approached the climb. I told Gen during breakfast that my only goal was to keep moving. Seeing this as the last major climb of the trip I wanted to test my fitness. I told her that I wasn't going to sprint but that I intended to go at a good pace without stopping until I reached the top. She nodded and told me she would meet me up there and with that I was off. I had prepped my phone with the Spotify playlist that had carried me through Kansas and Nevada. Rage Against the Machine's eponymous first album began on loop and I started motoring in the highest gear I could maintain a 90 rpm cadence comfortably.

The ride went by without difficulty. It was almost easy and I was smiling everytime a passing car held out a thumbs up or beeped encouragingly. This hill that I had envisioned as some gauntlet I'd have to fight to overcome had turned out to be one of the most pleasurable rides on the trip. I remember fighting the bike actively on other days, struggling to muscle its corpulence up previous hills. Today the bike just went the direction I pointed it. It's like when you have a good day climbing, you just find a rhythm and everything fits. You're already setting up for the next move before you've even finished the last. One position flows into the next. It was like that pedaling up Tioga, 90 revolutions a minute, comfortably sailing into the Sierras whilst being engulfed by beauty.

I reached the top only 2 hours after starting. We had originally anticipated the climb taking us the better part of half a day and it was over before lunchtime. The expected four miles an hour had been closer to six and I felt nothing in the way of exhaustion. Only more eagerness to continue into the park and reach a destination that had been tickling the back of my brain since the previous summer. I waited at the threshold of the park and had the woman at the gate process an interagency pass so that we would be all set to enter when Gen arrived.

In short order Gen joined me, having opted to bike like a sensible human being, and stopping to take pictures and refill water. She was equally exuberant and told me the climb had been way easier than she expected. A 'hill for babies' as we had come to call them, figuring that making fun of hills was the best way not to be afraid of them. We high-fived and made our way into Yosemite National Park.

Yosemite represents the tremendous dichotomy of our National Parks System. It is simultaneously a place of incomprehensible beauty and wilderness while also being a congested tourist trap. All of the things that make it an incredible park, make it an incredibly overvisited and busy park. RV's, motorcycle caravans and oversize vans abound. You can actually get stuck in traffic as you make your way through the sometimes unbearably busy park. In many ways, Yosemite's fame is its downfall, leaving you feeling like you're in an amusement park more than a wilderness. Chris Wood had characterized it as a zoo the previous year and it felt no different this time around.

We passed by Lembert Dome which I had photographed the previous year at dawn as we had entered the park. I told Gen our best bet for food was Tuolumne Meadows Campground and we stopped in for a quick bite. After lunch we opted to continue down 120 as we were well-ahead of schedule.

I might sound like a broken record but I really cannot do much to describe Yosemite without continuing to remark on its stunning beauty. The exposed granite domes of Tuolumne jut out from the meadow landscape. Soaring pieces of rock that stand in stark juxtaposition to the otherwise flat terrain. In the distance, larger peaks carve jack-o-lantern smiles across the horizon and leave you wondering what John Muir must've thought when he first encountered the park's rugged beauty.

As we emerged from a long sweeping corner Lake Tenaya came into view. Throughout the trip I have lamented the fact that we did not go swimming when presented with opportunities. Well I was not missing this one and Gen was only too happy to join me for some relaxation. I ditched my bike clothes and donned my swimsuit (boxer briefs) before plunging into the frigid mountain water.

As I plodded around, I discovered large polished granite rocks on the otherwise sandy floor. My brother Karl and I both inherited a genetic imperative to move and disrupt any object not otherwise firmly secured. I began the brainless task of carrying, throwing and rolling any boulder or rock that I could manage to budge into a large collection. With little planning or competence I set about stacking the largest stones at the base and building a pile that eventually towered out of the water. I figured cairns were built elsewhere in the park, there was no reason I could see that there shouldn't be cairns in the water as well.

Gen photographed as I piled my rocks to the amusement of onlookers. I am certain a few children were jealous of my beautiful rock castle as it reached my shoulder in height. Precariously balancing the stones one on top of the next the spire became unsteady and started to rock as I continued building my miniature Tower of Babel. With the stones nearly over my own head, I delicately placed the final pieces and stood back to marvel at my construction. Just one more stone and it would be taller than me. I lifted the wet rock out of the crystal water and dripping, brought it to rest, defiantly on top. The rocks underneath shifted and in one catastrophic movement slid out from under one another. I jumped back to preserve my precious toes and watched helplessly as the rubble pile disappeared beneath the lake surface. Such is life. Some things in life we build just to see how long they will take to fall.

I piled the rocks once more to a more humble measurement and left the new cairn standing out of the water, ready for the next ambitious fellow to try his hand. Gen was eager to get our camping arrangements squared away and I agreed it was time to leave the lake. Initially, our plan had been to stay at Tuolumne Meadows but I reiterated the fact that unless we went into the Valley there would be no showers this evening. With the agreement that we should at the very least continue in the direction of the other campsites we set back out onto Route 120.

During our planning processes each day we would consult our elevation profiles to determine what level of difficulty we could expect. Similar to the graph at the top of the page we would be able to estimate where we would struggle and where we would find 'free miles'. In our evaluation of the trip into Yosemite, we determined that after Tioga Pass, the cycling afterwards would consist primarily of downhill. Gen's butt was getting to the end of its cooperative point and she was eager to be done cycling for the day. More-so while the road up to the pass had been easily negotiated with little traffic, the park proper had higher volume of motorists, on more narrow roads, with less shoulder. Gen was understandably less than excited to have impatient camper vans tailgating her, as we charged down steep hills with large drop-offs to our right. Several times she motioned with an outstretched arm to the car behind to back off. The roads were clearly not built with the intent of accommodating bikers and cars simultaneously and we were forced to ride primary on the downhills so as not to encourage unsafe passing on the twisting road. The steep sections of downhill were regularly interrupted by brief but equally steep 'spurs' which would leave us once again spinning away in our lowest gear while competing for road-space.

Gen bemoaned the climbing, citing our reconnaissance of elevation profiles.

"I thought you said it would be downhill?!"

I checked my Garmin and zoomed the profile out for the next 25 miles but the problem is scale compression. When you have huge changes in elevation (like our 3,000 ft climb at the start of the day) it becomes nearly impossible to see the 200-400' bumps afterwards; scale compression obfuscates the smaller obstacles. I tried to guess the number of spurs we would encounter but without zooming to a scale that was virtually unusable I could only see the next 4 or so miles at a time. With each revision of my "remaining spurs count", Gen grew progressively impatient. When we arrived at Tamarack Flat (my suggested campsite) and Gen realized that it was almost entirely downhill she balked at the prospect of staying there. I was eager to get into the Valley proper and didn't argue that we should pass it up. As we approached the turn-off to the valley, Gen voiced concern that it was too late to be contending with traffic and potentially traveling the narrow roads after dark if we took too long. I assured her it would be fine and that at a downhill coasting speed we would be there in no time. She impatiently reminded me that it was not all downhill and it could take us hours longer than I projected. Her mood was rapidly deteriorating and while it was mildly comical to listen to her play out disaster scenarios and worst-case what if's, I was less than eager to debate. I simply shrugged her off and said it would be fine. Maybe not the best partner attitude and argument resolution but I was too happy to be in Yosemite to care.

We turned onto the park loop and began our descent. Rocketing down the steep roads, sometimes in excess of the speed limit, cars behind, filed into a large queue as we sped along the narrow corridor. The road was not only alarmingly steep but riddled with pockmarks, lumps and irregularities that on more than one occasion bounced us out of our seats and left us clutching the handlebars with mortal fear. It's an unpleasant mental image falling off your bike at 40 mph with a 2 ton car in hot pursuit. Still the 1000' interval elevation markers continued to fall, as we lost altitude in a hurry.

With the harrowing segment mostly concluded, we stopped for a photo opportunity at the famous "Tunnel View" Late day sun was illuminating Half Dome and we couldn't have asked for a nicer sight. Still concerned about the prospect of biking in the park after dark we didn't linger and were back on our bikes as soon as the picture was snapped. Signs ahead instructed vehicles to turn on their headlights in the tunnels and I heard Gen groan as she no doubt recalled the news story we had heard in Nevada of the cyclist killed in a tunnel on US-50. Yellow sodium lights cast an eerie glow as we shot down the long carved out rock.

One tunnel down and a couple to go we were nearing the valley floor while arguing about my concept of 'flat' and 'downhill'. Gen was convinced that my memories of Yosemite were unreliable because I had traveled the park in a car the previous year and the supposed downhill section after Tioga had included some short but steep climbs. I told her I was confident that the valley was almost entirely flat and that she needn't worry. The site of the Merced River flowing in the opposite direction spurred more doubt as she commented on the tendency of water to flow downhill. The bickering continued as we neared the Park Loop at the valley floor.

Through the last tunnel and we were in the valley proper. The road offered an opportunity to breathe easy as we had made it down safely with daylight to spare. Gen's butt was really sore at this point but we only had 6 miles to go. To Gen's credit my butt was usually the one that hurt and I did the bulk of ass-complaints over the course of the trip. Nevertheless, I teased as we pedaled up the mild incline of the park loop towards the Yosemite Lodge and food. She said it would be only fitting if the dining hall had already closed and I laughed in response. We reached the Loft at the Lodge and ordered the highest calorie item they had on the menu: Meat Lasagna; which we ate without pause for respiration or taste.

Afterwards, we pedaled to Camp 4 where I was confident we could camp whether it was full or not. The ranger station wouldn't open until 8AM but as loaded cyclists I knew we would be granted leniency if someone were to see our unregistered tent. We reached Camp 4 and predictably the unoccupied ranger station had a sign that said FULL . We entered anyway and I set to finding a site that wasn't taken, or more importantly a bear-box we could share to at least stash our food. I approached a kind group of French climbers who, after hearing where we had traveled from, quickly whisked us to their site where they cleared a bear-box and a tent-site for us. We hit the dirt and prudently passed out, considerate of the fact that we would need to be in line for a first-come/first-serve site reservation early before Ranger Pinky arrived.